Nepal-India Relations: Nepal’s New Political Map and Aftermath

Dr. Krishna P Upadhyaya

Even during the lockdown caused by Coronavirus, a small number of Nepalese representing the different political parties gathered in South Harrow in London on 22nd May with an enlarged new political map of Nepal and protest. Due to corona virus, protest letters were sent to Indian High Commission in London by post, the process which was followed by the Nepali expatriates and diaspora communities in Cyprus, Qatar, Belgium, Portugal, and Spain. Irrespective of differences in their political stances, they came together. This indicates that whether or not they support the current government in Nepal in internal matters, they truly believe that historically the land included in the new map belongs to Nepal, and there was a continuous claim by Nepal, more persistently after the advent of the democratic system of governance in 1990.

A closer look at the social media postings by the Nepali diaspora communities indicates that they rightly understand that the Sugauli Treaty between sovereign Nepal and British India in 1814 states that land to the east of the Kali River belonged to Nepal. More importantly, they argue the Kali River in question is the bigger river stream to the east of which falls the land included in Nepal’s recent map. Some social media postings, even unearthed that old school books around 1957 (around 2014 BS) showed the area in Nepal’s map, people of the area voted in the general elections of 1958 (2015 BS), and even the government of Nepal ran census survey in the area and the people paid land revenue to the government of Nepal around that period. The reason for repeated mention of diaspora communities of Nepal is that it is a more or less common understanding of Nepalis of all shades of political life and backgrounds, and eventually it got internationalized bringing the issue into public knowledge outside Nepal.

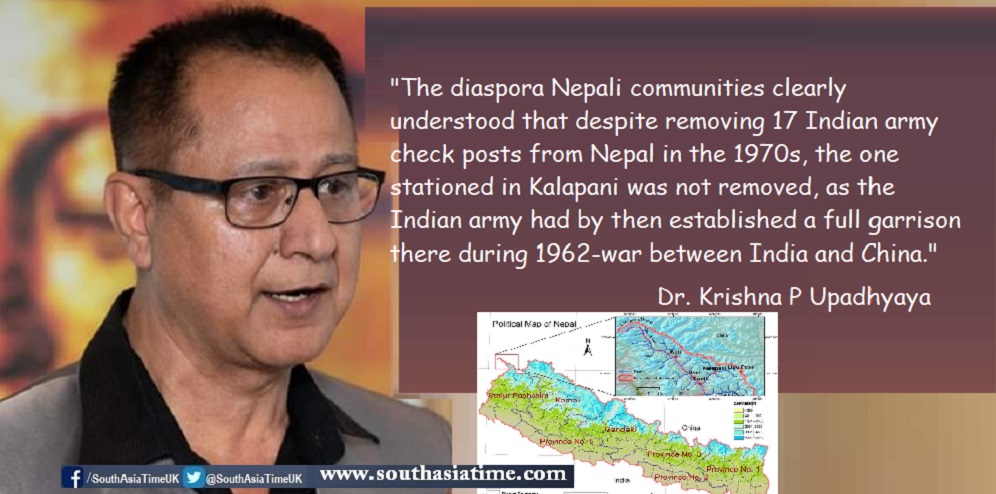

The diaspora Nepali communities clearly understood that despite removing 17 Indian army check posts from Nepal in the 1970s, the one stationed in Kalapani was not removed, as the Indian army had by then established a full garrison there during 1962-war between India and China. For nearly thirty years, the diaspora community believes as shown in their Facebook postings, there was no effort from governments of Nepal and did not raise the issue with their Indian counterparts, and around that time the area disappeared from Nepal’s map which was printed in India. Though anti-government political groups persistently raised the border disputes relating to Susta and Maheshpur during this period, the issue of Kalapani, Limpiadhura, and Lipulek (included in the current map) only came to public knowledge after the advent of democracy in Nepal in 1990. The diaspora community is also aware of the fact that Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala raised the issue with Indian counterparts in India, and the subsequent governments including that of Sushil Koirala brought the issue on the table with their Indian counterparts. Each time, they were assured that a joint survey team would look into the issue and it would be amicably solved through bilateral discussions.

The Nepali diaspora community is aware of the fact that Nepalis worldwide like the government of Nepal, their friends, and families in Nepal were taken aback when India and China agreed to use the tri-junction of Lipulek to open for India and China trade and pilgrimage in 2015. Nepal protested formally to both India and China. Diaspora Nepalese felt the pangs too. This had two-prong effects on the Nepali diaspora worldwide. Firstly, it made them rethink which they believed that China respects Nepal’s territorial integrity. No, not at the expense of their trade relationship with India. Diaspora community for the first time blamed Chinese for supporting India to use Nepali territory land, though indirectly. Secondly, they believed that though India accepts the historical map, mainly map created by British India regarding the border, the diaspora communities believed that Indians pointed to the smaller river as the Kali River, to justify their continued use of the land which is Nepal’s territory.

This idea echoed in November 2019 when India published its map after Kashmir was divided into two different states. That map clearly showed the area, which Nepal has been claiming, within Indian territory. The government of Nepal protested formally. Since then, Nepal has been making diplomatic efforts to have dialogue, which Nepal says, has been ignored by the Indian government. The dispute took a new high when Indian Defence Minister inaugurated the road linking the Chinese border which passes through the territory claimed by Nepal. This erupted the protests in Kathmandu. The government of Nepal called the Indian Ambassador in Kathmandu and protested with a diplomatic note. Subsequently, the Nepal government published a new map, which for the diaspora people, is re-incarnation of the old map used until 1957.

This is the context that makes all of them come together. All are not from Oli’s ruling party, and many vehemently criticize him when it comes to national politics. They are supporting the Oli government to initiate the bilateral dialogue with India and peacefully settle the issue, bringing the disputed land under Nepali administration.

Aftermath:

After Nepali decided to publish a new map, India’s Ministry of Foreign affairs reacted at a press conference and argued the 372 Square Kilometer land belonged to India. But at the same time, it also invited the Nepali side to resolve the issue through bilateral talks. Some television shows in India reacted angrily and also tried to stir nationalist feelings bringing Nepali Prime Minister’s comments made in the Nepali parliament, one of which is not related to the border dispute. Some other media outlets in India agree in Principle that under the agreement of 1814, the land east to Kali belonged to Nepal, but the river to them is the smaller river-let identified by India. One of the media shows even openly advocated for a hawkish step of toppling the Oli government. Their argument ran quite opposite to Nepali minds. At a time when Nepalis also blame China, the Indian argument is that the Nepali claim was made with Chinese backing. Showing some of the recent Chinese active roles within Nepal and increased collaboration and trade between two countries, India argues that the Chinese manipulation caused an artificial clash between India and Nepal, two ‘brotherly country’ with long shared cultural, religious and civilizational past, including economic, and family ties, popularly termed as ‘roti-beti’ relation. They argue Nepal is accessibly reliant on India due to its economic supports and trade, and but betraying India.

All true, but not the last one. Young and educated Nepalis have different interpretations to what Indians are saying. They believe that political rhetoric used by the leaders of both sides, may appear to be true in its face value but the internal dynamics are so much different that they call for carefully decided new relations between two countries. They argue the ‘roti-beti’ relation, trade, and changing context calls for a change of behaviours from the Indian side.

Information, and Interpretation

Let’s start with ‘roti-beti’.

Roti and Remittance: Thousands of Nepalis work in India, including in the army. This brings a sizeable remittance to Nepal. However, some recent studies show, India takes back threefold remittances from Nepal, which is the 8th biggest source for India’s foreign remittance. There are areas the migrants only can do the work in both countries. Most of the construction work in Nepal is the Indian sphere, but also the agriculture work in Uttarakhand is the Nepali sphere, as agriculture harvesting in the high altitude of the Uttarakhand cannot be done by workers in Bihar.

Beti: True. Until a few decades back Indian Royals either married off their daughters to Nepali palaces or also took grooms from Nepali royal houses. Culture, religion, language, and proximity, and to some extent, political relations, have contributed to this. Hundreds, if not thousands, of Brahmins, married in India after they completed their education in Gurukuls. This trend was high, until the 1960s. It continues albeit at a different level. Hill Nepalis still have marital relations with Nepali speaking Indians in the Darjeeling and Doors area of Bengal, Sikkim, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, and Mizoram, the state where first-ever Nepali modern school, known Gorkha High School, was established in 1922. There are also marital relations in large numbers with Maithili, Bhojpuri and Awadhi areas of both sides of the two countries.

Therefore, ‘roti-beti rista’ of Nepal with India is continued by both hill and plain communities of Nepal, as is the ethnic linkages. That is where India gets wrong. In India, it is commonly thought that primarily roti-beti and ethnic linkage is only with south Nepal.

Point to note here, ‘roti-beti rista’ is a relation of ‘sambandhi’ which is based on equal footing, not big-small notions. Two families in wed-lock respect each other in Indian and Nepali traditions. If politics has anything to reflect the society, the politics of bilateral relations must reflect this

Almost all common Nepalis understand Hindi, though the fluency varies. One should research how many Nepalis speak and understand Chinese. Similarly, common Indians can communicate with common Nepalis in their own languages, though the level of understanding the language may vary. This is why two countries have marriages between the common people from both rural and urban areas. It is not marriage between educated people with different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, say, between Brits and Filipinos. It is cultural on the plateau of religion, language, traditions, and acceptability. A Nepali or Indian girl going to a house as a groom in the other country, would certainly find the same pictures or deity in the prayer rooms which she sees in her parents’ prayer rooms, and recite the same prayer and hymns, and most probably in the same language. This is not the case with China. The relations with China are more political therefore simple and straight. Nepalis know they, as a nation, have still a long way to go to be able to use one country against the other. They know it and, therefore, don’t do it. They know China cannot be manipulated to use against India nor India can be manipulated. ‘China card’ is an old concept for Nepalis as it was the politics of the Royals during the 1950s/60s when they ushered to support one of the neighbours for their sustenance. Now, Nepal is politically open and it is irrelevant to a great extent. The fact is traditionally and culturally Nepal and India are so closely linked, the exploitation, misuse, and neglect will hurt both of them, the same as in the close-knit families or relatives. India, more than Nepal, should be sensitive to this. Because this relation will continue to be there in people’s levels. This must be reflected in the relations. Point to note here, ‘roti-beti rista’ is a relation of ‘sambandhi’ which is based on equal footing, not big-small notions. Two families in wed-lock respect each other in Indian and Nepali traditions. If politics has anything to reflect the society, the politics of bilateral relations must reflect this. The same is with the disputes which must be settled based on the logics and facts. Therefore, bringing China in between two countries’ issues hurts common Nepalis more than anything else.

Trade and Trade-Politics: Nepal being one of the biggest trade partners is a point of satisfaction for India. But the buzz during the TV debates in India that ‘we are giving them petrol, we are giving them rice” does not hold water, as it is not philanthropy, it is business, which India would like to continue. Nepali minds are very much aware of their uncomfortable position in the past that they had to trade only with India due to geographical advantage, language, and proximity. But when Nepal tries to diversify its trade with others, there is a buzz again from the backyard of India, which leaves Nepalis confused. Trade should go without politicking. That’s plain as that in plain Nepali minds.

Recognizing the historical realities, benefits of the trade to both parties, and entrenched ‘roti-beti’ and ethnic, linguistic, religious, and cultural linkages, Nepal and India should start bilateral discussions on the border issue sooner than later, without making room for any third party. The issue should be settled once and for all. For the better relations of the both countries, including for the control of crime and terrorism, they also must find forward looking solutions for the regulation of borders while still allowing people to people movement unabated. This serves the best interest of both the countries.

(A human rights researcher focusing on labor, migration, and social issues, Dr. Upadhyaya is Executive Editor of South Asia Time.)

Facebook Comments